How a Luxury Boom Is Changing New York’s Skyline

Pop quiz: How many residential buildings in New York City are over 800 feet tall?

The answer: 10. Six of them will be completed this year.

New York City is getting taller faster. Maybe you noticed this trend?

As my colleague Stefanos Chen wrote, by the end of 2019, several of the tallest new buildings in the city will be residential high-rises.

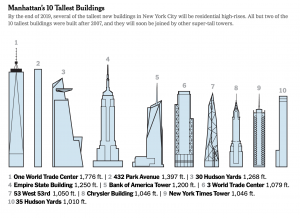

The escalation in elevation

Manhattan’s 10 Tallest Buildings

By the end of 2019, several of the tallest new buildings in New York City will be residential high-rises. All but two of the 10 tallest buildings were built after 2007, and they will soon be joined by other super-tall towers.

By the year’s end, these will be the 10 tallest buildings in New York City. All but two were built after 2007.

More are on the way.

An additional 16 towers — commercial and residential — are slated to be over 1,000 feet tall, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, a Chicago-based nonprofit that tracks high-rise construction.

Aren’t buildings here always getting taller?

Yes, but not this fast.

In 1908, the Singer Building in Lower Manhattan became the first in the city to rise above 500 feet. Since then, only 26 percent of buildings of that height were for residential use, according to the council.

[Read more about the transforming skyline.]

Since 2010, 64 percent of buildings (including those under construction) have been residential, most of them containing luxury condos, the council said.

Why are buildings getting taller?

One reason is technology.

Stronger concrete, faster and more efficient elevators, and sophisticated computer modeling have allowed developers to build taller and skinnier on sites that used to require much wider bases, according to Stephen V. DeSimone, the chief executive of DeSimone Consulting Engineers, who has worked on a number of new supertallbuildings.

Another reason is money.

Residential megatowers are becoming more common, marking what Mr. Chen called “a major shift from a skyline dominated by office space and executive suites to one increasingly focused on securing the best views for well-heeled residents.”

And well-heeled residents, apparently, want a room with a view.

“You can’t even start residential occupancy below 20 floors in a lot of these buildings, because the view has already been blocked,” said Daniel Safarik, an editor with the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.

Does the city regulate building heights?

Very much so.

Practically every inch of land in New York City falls into a zone that determines what kind of building can go there. Developers or landowners are sometimes granted waivers from those rules.

Lately, more developers are buying the unused development potential, or air rights, of adjacent properties to amass a larger building, Mr. Chen wrote.

Is this building too tall?

This building on the Upper East Side may be too large by about five floors, according to Gale A. Brewer, the Manhattan borough president, and a neighborhood group.

[Developers built a high-rise. They might have to chop off five floors.]

City officials approved the building’s plans four times. Officials said they would review them again after a challenge from the group, the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts.

Ms. Brewer said the structure — a 30-story condo tower under construction at Third Avenue and 63rd Street — included nearly 10,000 square feet that the city’s Department of Buildings should have never allowed.

If the building is found to be too large, a rare remedy could happen: amputation.

That could mean removing floors from the 467-foot-tall building to lower it. Another solution could be to take out ceilings in some units, which would reduce the building’s square footage.

As my colleague Matthew Haag wrote, the last time something like this happened in New York was in 1991, when a developer was ordered to reduce a 31-story building on East 96th Street to 19 stories.

Source: Azi Paybarah, The New York Times

USA 917-679-1211

USA 917-679-1211

© Jackson Lieblein, LLC 2015.

© Jackson Lieblein, LLC 2015.